The Headlines

Wright's "Fountainhead" Could Be Purchased By Mississippi Museum of Art

Fountainhead, a Frank Lloyd Wright–designed Usonian home in Jackson, Mississippi’s Woodland Hills neighborhood, is close to being acquired by the Mississippi Museum of Art (MMA). On October 23, the Jackson Planning and Zoning Board recommended approval of a zoning variance that would allow the house to operate as a museum for public tours and special events. The City Council and the Woodland Hills Neighborhood Association still need to finalize approvals, but neighborhood support has so far been unanimous.

The MMA plans to spend about $2 million to purchase the property and another $2 million to restore it to museum standards. The home, built in 1948, reflects Wright’s philosophy of organic architecture, with a parallelogram-based design integrated into the landscape, Heart Tidewater Red Cypress interiors, and all-original Wright-designed furniture included in the sale.

Fountainhead’s last owner, architect Robert Parker Adams, who played a key role in restoring and preserving many Mississippi landmarks, passed away in July. If finalized, the project will place Fountainhead among other historically significant homes in Jackson open to the public, such as the Eudora Welty House and the Medgar and Myrlie Evers Home.

All Lit Up Like A Japanese Lantern

By 1941, the year Pope-Leighey House was completed, Frank Lloyd Wright had studied Japan for almost a half-century. He had become a serious collector of woodblock prints--even writing a book on the subject--and had won acclaim for his design of the Tokyo Imperial Hotel, one of the few buildings to survive the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923. On this special tour, visitors will discover how the famous American architect incorporated his love of Japanese art, architecture, and philosophy into Usonian homes, and how this East Asian influence shines in Wright’s Pope-Leighey House.

About the Tour Guide: Kristi Jamrisko Gross is Lead Guide at Woodlawn & Frank Lloyd Wright’s Pope-Leighey House in Alexandria, Virginia and also works as a museum educator for the Office of Historic Alexandria. She holds an M.A. in Art History from the University of Maryland, where she wrote her thesis on Dutch–Japanese material culture exchange in the 1600s. Prior to graduate school, she taught English in rural Japan through the JET Program and worked as a science and nuclear policy analyst at the Embassy of Japan in Washington, DC.

Tickets are $25 for adults and $12 for students (K-12).

Questions? Call (703) 780-4000 or email woodlawn@savingplaces.org.

Wright Homes Flying Off The Market

Oak Park, Illinois, known for its high concentration of Frank Lloyd Wright-designed homes, has seen a surge in demand for these architecturally significant properties this year. Several Wright houses, including the Elizabeth and Rollin Furbeck and Hills-DeCaro houses, sold quickly after hitting the market. Most recently, the Francis J. Woolley House at 1030 Superior found a buyer in less than 24 hours, listed by Greer Haseman and Chris Curran of @properties Christie’s International Real Estate.

Built in 1893, the Woolley House reflects Wright’s transition from Victorian to early Prairie Style design, featuring art glass windows and a distinctive turret. Over its long history, the home has served as a single-family residence, a boarding house, and was extensively renovated in the 1990s, with further updates to the kitchen, deck, and bathrooms in 2018–19.

Haseman attributes the current success of historic homes to sensitive modern updates, especially to kitchens and family spaces. She notes that Wright homeowners enjoy a strong sense of community and shared resources for maintaining their historic properties. With low housing inventory and strong buyer interest, she says Oak Park’s fall real estate market has been “shockingly busy,” with historic homes “selling like hotcakes.”

Iconic And renovated Alden B. Dow Home On The Market For Just Under $2M

An iconic Midland, Michigan home designed by renowned architect Alden B. Dow in 1951—located at 11 Snowfield Court—is on the market for $1,995,000. Known as “The Timber Teepee,” the A-frame residence was originally built for a piano-loving client, featuring a suspended second floor and open balcony for guests to enjoy performances.

The 3,848-square-foot home includes four bedrooms and four bathrooms and has undergone a top-to-bottom renovation over the past two years. Updates include a new kitchen and bathrooms, refinished woodwork, new wool carpeting, new roof, chimney, and copper gutters, plus high-end appliances from Miele, Bosch, Kohler, and Subzero.

Set on a 1.9-acre lot with new landscaping, the remodel preserves Dow’s original architectural vision while modernizing the home for contemporary living. Realtor Katrin Thorson described the renovation as “a gift to the Midland community.”

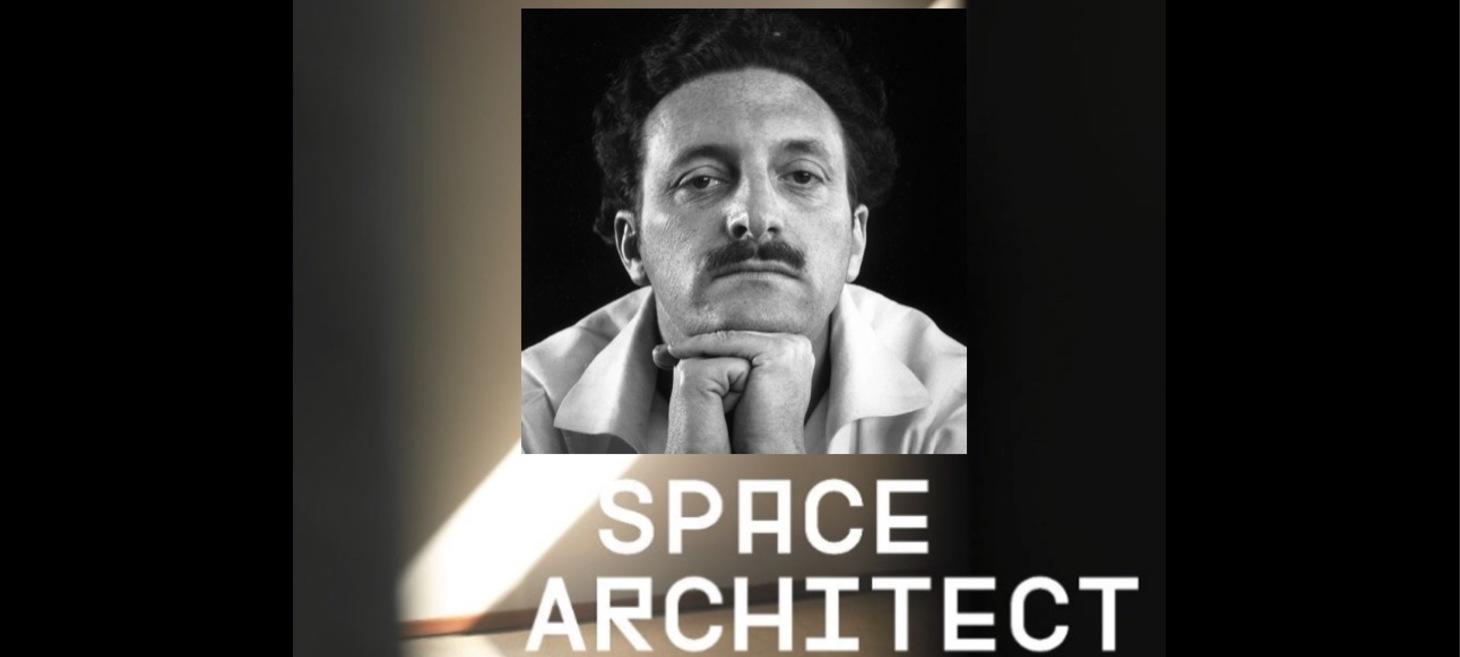

Being Schindler

Eric Preven, who lives in one of Schindler’s homes, the “Gold House,” in Studio City, California, pens a personal essay as a reflection on Schindler Space Architect—a new documentary about visionary modernist Rudolph Schindler.

It opens with a description of another nearby Schindler design, a 1949 courtyard apartment complex that epitomizes his inventive, human-centered approach to architecture. From there, Preven weaves together biography, film story, and lived experience, creating a portrait of Schindler as a radical who designed for feeling and space, not prestige.

The documentary, directed by Valentina Ganeva and narrated by Meryl Streep (with Udo Kier as Schindler), came together through a string of coincidences—a professor’s research into uncanny events, a casual mention of Streep’s name, and a serendipitous connection that brought the material to her. The film mirrors Schindler’s own sensibility: immersive, intimate, nonlinear—more like walking through one of his homes than watching a conventional biopic.

Preven situates himself among fellow Schindler dwellers (including writer Susan Orlean) and reflects on how living in such spaces reshapes one’s perception of design, creativity, and life. He admires the film’s tactile cinematography by Jacek Laskus and Danny Duchovny’s unhurried pacing, which honor Schindler’s belief in authenticity over perfection.

The essay closes by tracing Schindler’s humanism—his empathy in dealing with craftsmen, his blunt honesty with clients, and his complicated relationship with Frank Lloyd Wright. For Preven, Schindler’s legacy isn’t just architectural but moral: a call to live and work with conviction, to “draw the lines that matter,” and to defend meaningful spaces—whether in buildings, films, or civic life.

This is a meditation on Schindler’s enduring influence, a behind-the-scenes look at a documentary born from coincidence, and a personal testament to what it means to inhabit the world—and ideals—of a true original.

Smart Homes Of 2030: Blending Wright’s Organic Design With Modern Technology

Frank Lloyd Wright’s philosophy centered on creating architecture that lived in harmony with nature, humanity, and time. His buildings were not just structures but living experiences—compositions of proportion, light, and texture designed to serve life rather than dominate it.

If he were to design smart homes in 2030, Wright’s approach would transcend mere automation. He would weave technology seamlessly into the organic rhythm of daily life, creating architecture that feels and responds rather than simply obeys commands. His vision of “invisible intelligence” would produce homes that adjust to light, temperature, and emotion through empathy with their inhabitants.

Rooted in his lifelong mission to dissolve the boundary between indoors and outdoors, Wright’s future homes would use sustainable materials, responsive systems, and community-driven technologies. They would generate their own energy, harvest water, and share resources—embodying his democratic and ecological ideals.

Artificial intelligence, for Wright, would serve as a subtle extension of nature—a quiet apprentice that enhances comfort, beauty, and awareness. Instead of cold efficiency, his smart homes would express warmth and soul: light that shifts like sunlight, voices that echo natural tones, and scents that change with the weather.

Ultimately, Wright’s 2030 smart homes would reaffirm that technology should deepen human connection rather than replace it. His architecture would still seek harmony—between man and machine, nature and design—proving that the most intelligent buildings are those that feel as well as think.

About

This weekly Wright Society update is brought to you by Eric O'Malley with Bryan and Lisa Kelly. If you enjoy these free, curated updates—please forward our sign-up page and/or share on Social Media.

If you’d like to submit content to be featured here, please reach out by emailing us at mail[at]wrightsociety.com.